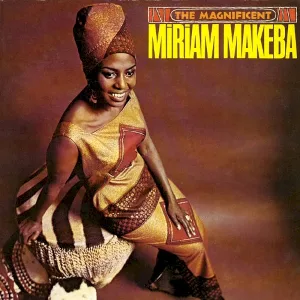

Miriam Makeba

Zenzile Miriam Makeba, nicknamed Mama Africa, was a South African singer and civil rights activist known for becoming the first African artist to globally popularize African music. Makeba was born in Johannesburg, South Africa on March 4, 1932.

Miriam Makeba began singing professionally in the 1950s, with the Cuban Brothers, South African jazz group the Manhattan Brothers, and an all-woman group, the Skylarks, performing a mixture of jazz, traditional African melodies, and Western popular music.

In 1959, Makeba had a brief role in the anti-apartheid film Come Back, Africa, which brought her international attention, and led to her performing in Venice, London, and New York City. While traveling to London she met Harry Belafonte who became a mentor and colleague and helped her gain entry into the United States. She moved to New York City, where she became immediately popular, and recorded her first solo album in 1960. Her attempt to return to South Africa that year for her mother’s funeral but discovered that her passport was cancelled, making her an exile. Later that year she signed with RCA Victor and released Miriam Makeba, her first U.S. studio album.

Throughout the 1960s she spoke out against apartheid in South Africa and later in the decade she met and married prominent civil rights leader and Black Panther Stokely Carmichael in 1968. They would laterdivorce in 1973. Makeba continued on in her activism and music career and in 1990 she would return to her home country of South Africa on a French passport after much persuasion by Nelson Mandela.

Activism

Makeba has also been associated with the movement against colonialism, with the civil rights and black power movements in the US, and with the Pan-African movement.

Makeba was among the most visible people campaigning against the apartheid system in South Africa, and was responsible for popularizing several anti-apartheid songs, including “Meadowlands” by Strike Vilakezi and “Ndodemnyama we Verwoerd” (Watch out, Verwoerd) by Vuyisile Mini. Due to her high profile, she became a spokesperson of sorts for Africans living under oppressive governments, and in particular for black South Africans living under apartheid. When the South African government prevented her from entering her home country, she became a symbol of “apartheid’s cruelty”, and she used her position as a celebrity by testifying against apartheid before the UN in 1962 and 1964. Many of her songs were banned within South Africa, leading to Makeba’s records being distributed underground, and even her apolitical songs being seen as subversive.

She called for unity between black peopleBlack People A term originally used to refer to people with dark skin complexions, generally to people of Sub-Saharan Afrikan ancestry but also to non-Afrikan dark skinned people, such as the Indigenous Australian and the Negrito populations of Thailand and the Philippines. of African descent across the world: “Africans who live everywhere should fight everywhere. The struggle is no different in South Africa, the streets of Chicago, Trinidad or Canada. The Black people are the victims of capitalism, racism and oppression, period”.

Legacy

Makeba’s 1965 collaboration with Harry Belafonte won a Grammy Award, making her the first African recording artist to win the award.

Makeba was among the most visible Africans in the United States; as a result, she was often emblematic of the continent of Africa for Americans. Her music earned her the moniker “Mama Africa”, and she was variously described as the “Empress of African Song”, the “Queen of South African music”, and Africa’s “first superstar”. Music scholar J. U. Jacobs said that Makeba’s music had “both been shaped by and given shape to black South African and American music”. The jazz musician Abbey Lincoln is among those identified as being influenced by Makeba.

A documentary film titled Mama Africa, about Makeba’s life, co-written and directed by Finnish director Mika Kaurismäki, was released in 2011.

In 2014 she was honored (along with Nelson Mandela, Albertina Sisulu and Steve Biko) in the Belgian city of Ghent, which named a square after her, the “Miriam Makebaplein”.

Responses